Story of Scrooge, ghosts and Tiny Tim is 175 years old ? and still incredibly powerful

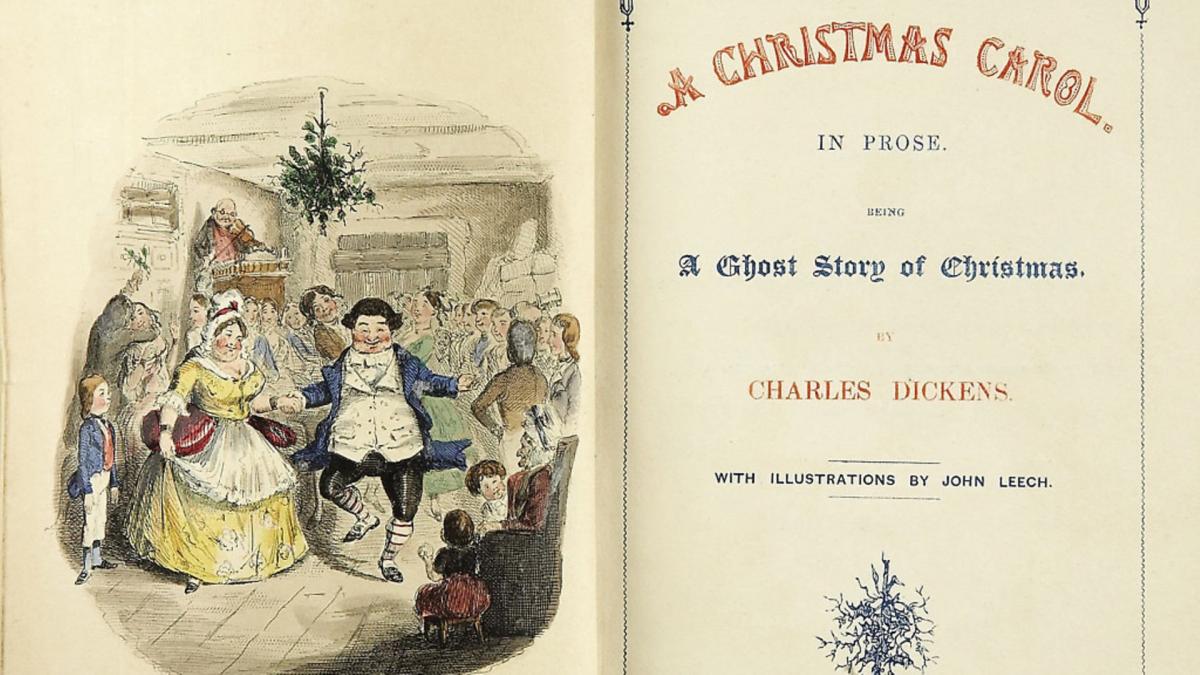

Charles Dickens didn’t quite invent Christmas, but he certainly stamped images on the public consciousness in such a vivid way that they endure today. Much is down to A Christmas Carol, 175 years young

Louisa Price is working late – perilously close to the hour when the clanking chains of ghost Jacob Marley might be heard, should you have eaten a dodgy piece of cheese. It’s a busy time for the curator of the Charles Dickens Museum, largely because this great English writer and Christmas are joined at the hip.

The London museum, one of the Dickens family’s former homes, really goes to town at this time of year. Its rooms are transformed into “Christmas Past” – the halls decked with holly and ivy and Victorian decorations evoking the 1800s. Visitors relish the sounds, sights and smells.

And then there’s Dickens’s story A Christmas Carol, with miser Ebenezer Scrooge and the ghosts that show him who he is and who he could be. It’s inspired countless films and TV adaptations. Towards the end of 2017 we even had the semi-fictional film The Man Who Invented Christmas.

Hmm. Perhaps CD shaped a version of it. In association with others.

We know about Prince Albert and the fir tree he introduced in 1841 – before Dickens wrote his novella in 1843. Henry Cole, founding director of the Victoria & Albert Museum, sent the first Christmas card that year. And sweet-seller Tom Smith of London is credited with inventing the cracker in 1847.

What we can say is that Charles Dickens parcelled up a lot of Christmassy components – the hand of friendship, the strength of the family bond, merriment, food, decorations, love, selflessness, hope and redemption – and “sold” it to the nation in a way that brought it to vivid and irresistible life. The writer’s skill captured people’s imaginations. Still does.

He probably did cement the link between the festive season and snow – perhaps remembering fondly a run of very cold winters from his childhood – and he did put charity at the heart of Christmas.

Suffolk historian and lecturer Clive Paine, a Dickens enthusiast, told me some years ago: “He almost invented our ideal Victorian Christmas, with his descriptions of the German Christmas tree and the fireside – but always as a novelist and always with a journalist’s view as well: trying to use the model not just to entertain but also to make social points.”

That’s key, for it’s much more than a ghost story with a happy ending for Tiny Tim, the rest of the Cratchit family and the reborn Scrooge.

“The brilliance of A Christmas Carol is that it is a reading-aloud and a read-in-one-sitting festive family story that captures its reader with a radical message about compassion for the downtrodden,” explains Louisa Price, from the Dickens Museum.

“In 1843, Dickens had been brooding on a range of societal issues: from child labour, education for the working classes and the care of the poor.

“He had initially intended to write a political tract on the topic, but changed his mind and wrote this Christmastime novella, which he believed would ‘strike a sledgehammer blow’ on behalf of the poor with more impact than any pamphlet.

“He was right. Dickens summed up his intent in the book’s preface, where he describes the theme as ‘A ghost of an idea’, and desires for readers that ‘it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it’.”

It seems there was also a commercial imperative. He’d had four successful novels (The Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby and The Old Curiosity Shop) but Barnaby Rudge hadn’t proved such a hit. Martin Chuzzlewit, which had been coming out in monthly instalments since early in 1843 and still had more than six months to run, also hadn’t captured the imagination quite so brilliantly.

Dickens, not yet 32 but the breadwinner for a growing household that wasn’t cheap, wrote the 28,000-word-ish novella in six weeks in the early winter of 1843, with Christmas his deadline.

It was published (he brought it out himself) on December 19, 175 years ago, and sold about 6,000 copies in six days.

“A Christmas Carol was an instant hit,” Lauren Laverne wrote in The Guardian in 2014. “It didn’t make Dickens rich (the author’s fault – he insisted on the idealistic combination of top-spec packaging and a low price…) but it forever tied him to the season.”

William Wallond, treasurer of Southwold & District Dickens Fellowship, takes a similar view.

“A Christmas Carol was immediately popular when first published and its popularity has continued unabated ever since. And no wonder: it appeals to people on so many levels.

“It is a ghost story; it campaigns against poverty, ignorance and injustice; it shows how the most reprobate and selfish can be redeemed by Christian charity and kindness; and it celebrates both the festive traditions and the true meaning of Christmas.”

Charles Dickens’ novel is still relevant today

“I had my ideas about right and wrong when I was child, yet I had no social conscience. A Christmas Carol was one of the books that changed that.”

Lest anyone doubt the power of Charles Dickens, see what else Robert Welton has to say. He’s librarian at Jane Austen College in Norwich.

“As time moved on and I got older it’s become more obvious that Charles Dickens’ novel is still relevant today.

“It’s more than a gothic story of poverty, though. The central story of Scrooge’s redemption is just about being kind and looking after those who need a little more help. “One hundred and seventy-five years ago Dickens wrote a nice little book with grumpy old Scrooge to remind us of our social conscience – calling on Victorian England, and right through to 2018, to be compassionate towards the less fortunate.”

Chelmsford ‘the dullest and most stupid place on earth’

Charles Dickens was no stranger to our region. In 1835, while covering election meetings for a newspaper, he told a friend that Chelmsford was “the dullest and most stupid place on earth” – a town where, apparently, he could not find a newspaper on a Sunday.

Dickens also went to Braintree, Sudbury, Colchester and Bury St Edmunds on journalism duty. Later, East Anglia would feature in some of his novels, such as Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield.

The author frequently toured the country to read his works, too. On October 13, 1859, he was at The Athenaeum in Bury St Edmunds – reading from A Christmas Carol and the trial from Pickwick.

* The Charles Dickens Museum is definitely worth a visit. It’s at 48 Doughty Street, London, WC1N 2LX. dickensmuseum.com

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here